Recent writing on the Russo-Ukrainian crisis often frames the conflict as a war that hasn’t happened yet but might occur at any moment. But Russia’s hybrid warfare doctrine sees things quite differently. Far from being a potential future war, the conflict might have started already – indeed, its decisive phase may be happening now.

Decisive 'shaping' to defeat adversaries

Russian planners regard pre-combat “shaping” – political destabilisation, cyberattacks, electronic warfare, sabotage, manipulated unrest, economic and energy disruption – as decisive. Following a method some call “new-generation war”, they seek to defeat adversaries before the first tank rolls or the first missile is launched. Actual combat, in this construct, consolidates victories that have already been won during the shaping stage. Conversely, if Moscow can achieve its goals during this pre-combat phase, the tanks may never roll.

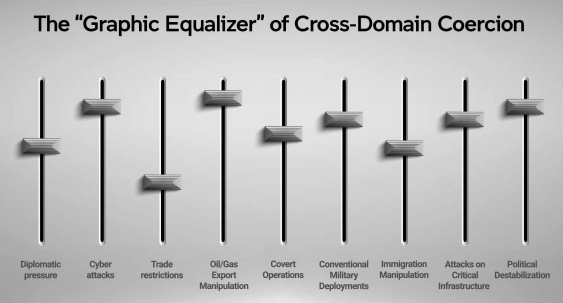

As a result, rather than seeing today’s problem as one of deterring a possible future war, it is useful to consider the conflict as one that is playing out now, through measures short of combat – something I described in a 2020 book as “liminal warfare,” and other analysts have called “grey zone conflict” or “cross-domain coercion”. Pre-combat shaping seeks to de-stabilise, disrupt and coerce adversaries, divide allies politically and economically, force concessions through intimidation, and achieve goals that would otherwise require open warfare. We can visualise Russian cross-domain coercion as a graphic equalizer, with each dial representing a form of pressure that can be adjusted up or down:

Illustration: based on original artwork by David J. Kilcullen

Many of these forms of coercion are evident now. For example, Ukraine suffered a major cyber-attack in mid-January, targeting government websites. A month earlier Poland and Lithuania – regional supporters of Kyiv with strong historical ties to western Ukraine – suffered manipulated inflows of undocumented migrants across their border with Russia’s ally Belarus, following a pattern that dates back to at least 2015. Russian troop deployments now total more than 127,000 around Ukraine’s borders, while Russian reservists are being mobilised, specialist medical and logistic units are deploying to the border, and six Russian amphibious ships – drawn from the Russian far east and the Baltic Fleet – are sailing through the Mediterranean to the Black Sea, increasing the perception of impending conflict (and simultaneously drawing attention away from covert operations and sabotage action against Ukrainian targets).

Information operations in Russian- and Ukrainian-language outlets and on social media are ratcheting up, while political destabilisation attempts (setting ethnic, linguistic and regional groups against each other) are ongoing. Further afield, Russia’s diplomats in the UN Security Council and in direct talks with the United States, EU and NATO are working to split NATO allies from each other, divide the EU’s interests from those of NATO, and pressure key countries such as Germany and France. Economic coercion – via manipulation of Russian oil and gas, which account for 40% of EU energy imports and much of Europe’s household heating – threatens millions of people in midwinter.

In effect, Moscow is working the dials on the graphic equalizer of cross-domain coercion, seeking to split NATO, divide Europe, force Washington to back down, intimidate Kyiv and thereby achieve key political goals – pushing back NATO presence in Eastern Europe, limiting Ukraine’s sovereignty and territorial integrity, exercising a tacit veto over its neighbours – without having to fight.

If combat occurs in Ukraine, what will happen?

Although the current pre-combat phase may turn out to be decisive, it’s important to think forward to what actual combat might look like, since communicating an image of imminent conflict is a key aspect of Russian intimidation tactics. Russia’s troop dispositions, the makeup of its forces around Ukraine’s periphery, and the weapon systems being deployed give a clear picture of how a hypothetical combat scenario might play out.

The first stage would likely be what Russian planners call “non-contact warfare.” Initially, this would include increased cyberattacks on Ukraine’s electrical grid, communications systems, critical infrastructure and transport systems, and cutting off energy supplies to Ukraine, Western Europe and possibly to the United States, which gets about 11% of its crude oil and petroleum products from Russia. Electronic attacks to jam military communication systems, GPS and mobile phone systems would be the last non-kinetic option short of the threshold of combat, and would likely be followed by a pause to negotiate as Russia seeks to secure its objectives without fighting (and as NATO and Ukrainian leaders determine whether to impose sanctions, and/or respond with cyberattacks or other non-kinetic moves of their own).

Read more: Are lethal autonomous weapons the future of warfare?

Absent a negotiated solution, the conflict would then cross the kinetic threshold, with Russian missile strikes on Ukrainian military bases, harbours, logistics depots, airfields and transport hubs. Bridges across key rivers or within urban areas might be targeted. These would be non-nuclear strikes, but delivered en masse to defeat defences through sheer volume. Areas near contested cities such as Mariupol, Kharkiv and Odessa would also be likely targets, aiming to isolate urban areas from electricity, gas and food supplies.

In this context it’s worth noting another Russian concept: the “interchangeability of fires and forces”. Russian planners treat missile strikes, electronic warfare hits or cyberattacks as equivalent to manoeuvre units such as Brigades or Battalion Tactical Groups (BTGs), the building block of Russian ground forces. Likewise, they treat “non-kinetic” electronic or cyber strikes as equivalent to “kinetic” strikes using artillery or aircraft, drawing from multiple sources to create an integrated effect. This allows a larger weight of firepower (kinetic or non-kinetic) to compensate for lack of mass, and vice versa. This is one reason why the relatively small Russian forces deployed on Ukraine’s border – less than half the number needed to secure a country of 40 million people against active opposition – does not in itself prove Moscow is bluffing. Other capabilities need to be taken into account, as part of an overall “correlation of forces” calculation.

The relatively small presence of Russian troops, such as these photographed in Red Square in 2019, on the border with Ukraine does not suggest Russia is bluffing. Photo: Shutterstock

The next stage would likely involve an intensifying air campaign, with Russian aircraft suppressing Ukrainian air defences, striking air bases and aiming to catch the Ukrainian air force on the ground or destroy Ukraine’s relatively small fleet of Su-27s and MiG-29 interceptors, to gain air superiority ahead of a possible ground move. Again, Moscow would likely pause here, offering an off-ramp to a negotiated settlement ahead of any ground invasion. By this point, of course, thousands of Ukrainians and dozens of Russians would have been killed, even if Ukraine had not directly retaliated, leaving passions high and a negotiated outcome increasingly hard to achieve. Russia’s goal in this phase would be to intimidate Kyiv and show NATO/US impotence, encouraging Ukraine to sue for peace.

Failing such a negotiated settlement, a ground assault could commence, combining so-called “coup de main” operations by airborne and special operations forces seizing critical chokepoints and then fast-moving conventional armoured units moving rapidly to link up with them and consolidate control. Ukraine has capable missiles of its own, along with anti-armour and artillery systems which would worry Russian commanders. Perhaps Ukraine’s most dangerous capability in Russian eyes would be the suite of Turkish-made drones and loitering munitions it has been acquiring with help from Ankara. The late-2020 conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh, where Turkish-made loitering munitions in the hands of Azerbaijani forces proved devastating against Armenia’s Russian-made armoured vehicles, emphasized the effectiveness of these systems and the risks they pose to Russian forces, making drone launching sites a primary target.

Read more: The internet is now an arena for conflict, and we're all caught up in it

Any ground assault would also probably combine guerrilla and terrorist attacks against Ukrainian positions from the rear with artillery-supported armoured thrusts from the front and flanks. An amphibious assault on the southwestern city of Odessa, combined with attacks from Russian-controlled Crimea, is one likely move, while a south-eastern offensive from the separatist Donbas region to seize Ukraine’s Black Sea coast and thereby establish a land corridor linking Crimea with southern Russia is another possibility. A northern offensive from Belarus, targeting Kharkiv, is also possible – although, again, Moscow would probably pause after each major offensive thrust seeking a political settlement. A final assault against Kyiv (likely from Belarus from the northwest in order to avoid a potentially difficult assault crossing of the Dnepr River) would represent the last stage of a conventional ground offensive – though not the end of the war, as a protracted insurgency and urban resistance warfare campaign would almost certainly follow, and could tie hundreds of thousands of Russian troops down indefinitely.

Indeed, western special forces and intelligence agencies have been training and supporting Ukrainian civilian resistance groups for exactly this purpose, while civilian resilience – including preparations for guerrilla warfare against occupation forces – has been a focus for Kyiv, because it emphasizes the cost of conflict for Russia and thus has a deterrent effect.

Hybrid warfare, if possible, seems Russia's goal

Again, none of the above is particularly likely. The most likely case is that the conflict has already started, in a hybrid warfare sense, that much of the war talk (on both sides) is best interpreted as posturing and signalling, and that actual combat remains relatively unlikely. Indeed, communicating an image of the situation to Western planners – part of a process of political warfare that Russian planners call “reflexive control” – is a key aspect of Russian hybrid war, designed to intimidate and coerce without actually resorting to combat. But, of course, when nuclear-armed powers play games of brinksmanship, there is always the chance of miscalculation or miscommunication. Should combat occur, Russian casualties would be high – perhaps unacceptably so, even in the event of a Russian victory – while the risk of further escalation into a direct conflict with NATO would be hard for Russian planners to rule out. The preponderance of evidence thus suggests, rather, that Moscow means to achieve its goals through pre-combat shaping, cross-domain coercion and its suite of hybrid warfare tools rather than through combat per se.

David Kilcullen is co-leader of the Future Operations Research Group, UNSW Canberra, and Professor of International and Political Studies, School of Humanities & Social Sciences, UNSW Canberra.